Sorry once again for the lag between posts. I've been busy with Globe projects that have kept me away from here. That said, I am planning for 2007, when I hope to do a full relaunch of this blog, complete with a new design, better content and a few of the best and brightest business and personal finance writers from around the country as contributors -- look for the first posts from our first new contributor, Tory N. Parrish, a business reporter from upstate New York, before year's end. Until then, bear with me and pardon the dust as I spruce up the place a little bit. Thanks for reading.

-KR

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Wednesday, November 08, 2006

Back to the hood again, part II

One of the best parts of my job is interacting with some of the most successful businesspeople in America. In the last 48 hours alone, I had one-on-ones with the vice chairman of one of the largest banks in the country, the entrepreneur who founded a successful private jet company backed by Warren Buffett himself, and a man who owns professional basketball and hockey teams.

One of the common threads between them all, besides being filthy rich is that they're all white guys, and to a person, they're all cool with talking about provocative topics like race, which has made for some interesting conversations. Which brings me to today's topic -- actually, a follow-up to my last post about how dismal the neighborhood I grew up in in Pittsburgh looked when I visited a few weeks ago, and what could be done to change it.

I brought this up during yesterday's meeting with the bank vice chairman as we chopped it up about our backgrounds, educations, and what inspired us to do what we do. I told him how profoundly growing up in a neighborhood that hadn't seen any new jobs, homes or investments in my lifetime had affected me and influenced my ambitions in life, then he told me a story of his own about a similar neighborhood.

It was Boston, circa mid-1990s. Like my neighborhood in Pittsburgh and hundreds of other high-minority, low-income neighborhoods around the country, the Dorchester section of Boston was suffering under the weight of drugs and gang violence fueled by disinvestment. Sturdy buildings and solid houses stood vacant, almost screaming for entrepreneurs and families to make something useful out of them and make a profit in the process. Finally, the business community in Boston, the black clergy, the mayor decided enough was enough.

As the story was told to me, a crew dozens strong got together and went to Codman Square, at the time a particularly dilapidated part of Dorchester, and slept overnight in an abandoned building there -- a symbolic gesture that if a bunch of preachers and rich downtown white guys would sleep there, then maybe there was hope for the neighborhood. A few bankers, including the one I met with, made a point of lending money to entrepreneurs who would open up businesses there and giving loans to families who wanted to buy houses. A decade later, I live just about a mile from Codman Square. The neighborhood still has its problems, but people on the street tell me it's a thousand times better than it used to be. Houses around here (though overpriced and perhaps even teetering on even more steep value drops) are selling in the $400,000 to half-a-mil range.

Ok, so what's the point? Well, after my last post, I got quite a few emails from people like myself -- young, black professionals who left Pittsburgh in droves in the last decade to get away from suffocating neighborhoods like my own. And the common question I've gotten has been this: "Is Boston as racist as I heard it is? Is it as bad as the racism in Pittsburgh?"

It's a question that bothers me in the wake of what I saw at home and after my conversation with the banker -- not because I'm naive enough to think that racism doesn't exist, but because so many of the problems in our neighborhoods didn't start and won't end because of any white person's prejudices. Along Lincoln Ave., the main drag through my neighborhood back home, not even the barber shops or corner stores that were open when I grew up there survived. Vacant buildings and houses potentially worth hundreds of thousands of dollars get no more attention than the few cats who bother to stand in front of them and sell drugs. And half of them are my age, still in the same spot I last saw them in high school.

So sure, racism's a problem in my hometown and where I live now, but it ain't the number one problem we got if a bunch of white men are willing to sleep in abandoned buildings to help turn a black neighborhood around in one city, while in another, black males would rather pitch $20 cracks than buy and sell buildings that could turn their own lives, and so many others', into something better.

In another conversation in my senior year of college, a black investment banker who led what at the time was the only black-controlled company of its kind that was publicly-traded, told me something else that I remembered this week. He said: "The civil rights movement of your generation is economic." Truer words were never spoken. My mother's generation, and her mother's, may have had whitefolks' racism as a primary obstacle to what they could do in life, but I don't. Sure there are and will always be those who don't want to see a brotha, a sista, or a 'hood be anything good, but if there was anything that limited anybody from around my way from being successful, it had way more to do with the fact that my neighborhood was losing that economic battle, big time. A decade later, I'm in control of my own destiny because I want to be -- not because some white guy said I could or couldn't. Sad thing is, I still can't say the same for my old 'hood.

One of the common threads between them all, besides being filthy rich is that they're all white guys, and to a person, they're all cool with talking about provocative topics like race, which has made for some interesting conversations. Which brings me to today's topic -- actually, a follow-up to my last post about how dismal the neighborhood I grew up in in Pittsburgh looked when I visited a few weeks ago, and what could be done to change it.

I brought this up during yesterday's meeting with the bank vice chairman as we chopped it up about our backgrounds, educations, and what inspired us to do what we do. I told him how profoundly growing up in a neighborhood that hadn't seen any new jobs, homes or investments in my lifetime had affected me and influenced my ambitions in life, then he told me a story of his own about a similar neighborhood.

It was Boston, circa mid-1990s. Like my neighborhood in Pittsburgh and hundreds of other high-minority, low-income neighborhoods around the country, the Dorchester section of Boston was suffering under the weight of drugs and gang violence fueled by disinvestment. Sturdy buildings and solid houses stood vacant, almost screaming for entrepreneurs and families to make something useful out of them and make a profit in the process. Finally, the business community in Boston, the black clergy, the mayor decided enough was enough.

As the story was told to me, a crew dozens strong got together and went to Codman Square, at the time a particularly dilapidated part of Dorchester, and slept overnight in an abandoned building there -- a symbolic gesture that if a bunch of preachers and rich downtown white guys would sleep there, then maybe there was hope for the neighborhood. A few bankers, including the one I met with, made a point of lending money to entrepreneurs who would open up businesses there and giving loans to families who wanted to buy houses. A decade later, I live just about a mile from Codman Square. The neighborhood still has its problems, but people on the street tell me it's a thousand times better than it used to be. Houses around here (though overpriced and perhaps even teetering on even more steep value drops) are selling in the $400,000 to half-a-mil range.

Ok, so what's the point? Well, after my last post, I got quite a few emails from people like myself -- young, black professionals who left Pittsburgh in droves in the last decade to get away from suffocating neighborhoods like my own. And the common question I've gotten has been this: "Is Boston as racist as I heard it is? Is it as bad as the racism in Pittsburgh?"

It's a question that bothers me in the wake of what I saw at home and after my conversation with the banker -- not because I'm naive enough to think that racism doesn't exist, but because so many of the problems in our neighborhoods didn't start and won't end because of any white person's prejudices. Along Lincoln Ave., the main drag through my neighborhood back home, not even the barber shops or corner stores that were open when I grew up there survived. Vacant buildings and houses potentially worth hundreds of thousands of dollars get no more attention than the few cats who bother to stand in front of them and sell drugs. And half of them are my age, still in the same spot I last saw them in high school.

So sure, racism's a problem in my hometown and where I live now, but it ain't the number one problem we got if a bunch of white men are willing to sleep in abandoned buildings to help turn a black neighborhood around in one city, while in another, black males would rather pitch $20 cracks than buy and sell buildings that could turn their own lives, and so many others', into something better.

In another conversation in my senior year of college, a black investment banker who led what at the time was the only black-controlled company of its kind that was publicly-traded, told me something else that I remembered this week. He said: "The civil rights movement of your generation is economic." Truer words were never spoken. My mother's generation, and her mother's, may have had whitefolks' racism as a primary obstacle to what they could do in life, but I don't. Sure there are and will always be those who don't want to see a brotha, a sista, or a 'hood be anything good, but if there was anything that limited anybody from around my way from being successful, it had way more to do with the fact that my neighborhood was losing that economic battle, big time. A decade later, I'm in control of my own destiny because I want to be -- not because some white guy said I could or couldn't. Sad thing is, I still can't say the same for my old 'hood.

Saturday, October 28, 2006

A letter from home, $75 Timberlands

Sorry, again, for not posting for so long. Between helping launch an online project for the business section of the Globe, transitioning to a new beat writing about sports business and banking (which will both make for some good posts here), and some family drama, it's been hard to keep up.

This entry comes from my hometown of Pittsburgh. Besides having the greatest football team on Earth, Pittsburgh is a little like the land that the economy forgot. That's both good -- a decent house can still be had here for far less than $200 grand -- and bad, because many neighborhoods here, especially black 'hoods, haven't seen a new job, store or anything else in years. Ain't been a house built or a business opened around my way in my lifetime -- and I'll be 30 three months from now.

That said, I owe a lot of my own ambition, if not career success, to the 'Burgh's sorry economy. If I hadn't watched my overeducated mother and hard working aunts and uncles struggle to make ends meet here, and watched my own neighborhood slowly disintegrate under the weight of disinvestment, I may likely not have had the motivation or the stones to go away to college, land jobs in politics and journalism and end up at one of the biggest newspapers in the country while in my 20s.

But as an adult who makes his living writing about how people make money, coming home to see the fam and riding through my old hood is a crazy mix of depressing and ridiculously encouraging. Depressing because the fam still struggles -- peep how my uncle who picks me up from the airport runs down how he's out of work and trying to hold it down for his wife and kids, and because the neighborhood looks worse than ever, with no fewer than half the buildings on The Ave. (don't ask which one, it could be almost any Ave from Brooklyn to Watts) standing empty.

Those buildings, though, are the reason why I'm optimistic, perhaps foolishly. I mean, if anybody had a solid plan and any cash at all, they could make something out of those buildings, like a store or two since there are none for people to walk to, or some decent apartments in an abandoned school, or a renovated single family in a solid brick building that nobody's called home for years. Hell, how bout a salon, cuz damn if black folks are goin' spend their money on anything, it's going to be looking good!

If I had any money of my own, I'd definitely give it a go. Anybody have a story about what it looks like around your way?

A coupla sidenotes: I bought my 9-year-old son a pair of $75 Timberlands today. Did I do wrong? I mean, under normal circumstances, I let my boys pick out their own clothes, within reason. I'm definitely not raising label whores here, but I'm not of the mindset that the best way to teach kids to save instead of spend is to deprive them of any and everything just for the sake of them hearing Daddy say "no". Still, I normally wouldn't have paid that much for a pair of shoes for a nine year old. Thoughts?

Meanwhile, my seven-year-old sees me writing this and wants to know what I'm doing. Daddy is writing for a web site that he owns, I said. "That you own? You mean you're the boss of yourself? That's stupid!" he said. Apparently, that little one has a lot to learn.

This entry comes from my hometown of Pittsburgh. Besides having the greatest football team on Earth, Pittsburgh is a little like the land that the economy forgot. That's both good -- a decent house can still be had here for far less than $200 grand -- and bad, because many neighborhoods here, especially black 'hoods, haven't seen a new job, store or anything else in years. Ain't been a house built or a business opened around my way in my lifetime -- and I'll be 30 three months from now.

That said, I owe a lot of my own ambition, if not career success, to the 'Burgh's sorry economy. If I hadn't watched my overeducated mother and hard working aunts and uncles struggle to make ends meet here, and watched my own neighborhood slowly disintegrate under the weight of disinvestment, I may likely not have had the motivation or the stones to go away to college, land jobs in politics and journalism and end up at one of the biggest newspapers in the country while in my 20s.

But as an adult who makes his living writing about how people make money, coming home to see the fam and riding through my old hood is a crazy mix of depressing and ridiculously encouraging. Depressing because the fam still struggles -- peep how my uncle who picks me up from the airport runs down how he's out of work and trying to hold it down for his wife and kids, and because the neighborhood looks worse than ever, with no fewer than half the buildings on The Ave. (don't ask which one, it could be almost any Ave from Brooklyn to Watts) standing empty.

Those buildings, though, are the reason why I'm optimistic, perhaps foolishly. I mean, if anybody had a solid plan and any cash at all, they could make something out of those buildings, like a store or two since there are none for people to walk to, or some decent apartments in an abandoned school, or a renovated single family in a solid brick building that nobody's called home for years. Hell, how bout a salon, cuz damn if black folks are goin' spend their money on anything, it's going to be looking good!

If I had any money of my own, I'd definitely give it a go. Anybody have a story about what it looks like around your way?

A coupla sidenotes: I bought my 9-year-old son a pair of $75 Timberlands today. Did I do wrong? I mean, under normal circumstances, I let my boys pick out their own clothes, within reason. I'm definitely not raising label whores here, but I'm not of the mindset that the best way to teach kids to save instead of spend is to deprive them of any and everything just for the sake of them hearing Daddy say "no". Still, I normally wouldn't have paid that much for a pair of shoes for a nine year old. Thoughts?

Meanwhile, my seven-year-old sees me writing this and wants to know what I'm doing. Daddy is writing for a web site that he owns, I said. "That you own? You mean you're the boss of yourself? That's stupid!" he said. Apparently, that little one has a lot to learn.

Monday, October 09, 2006

Not by any means...

A friend and reader asked me recently why I thought members of other ethnic groups tend to buy their first houses at an earlier age than we do.

Her theory: "I think it's lack of encouragement. I didn't think owning property was a big deal until my dad badgered me my entire year and a half of grad school to buy something small when I get my first job."

I think there are any number of reasons why we tend to buy our first houses later in life than other groups. First, beware the generalizations -- I know a few black folks my age (in the vicinity of the late 20s, thank you), who already own their houses and have for a few years. At least one person I know owns more than one property. And not every white person, of course, buys their first house in their early 20s.

That said, one obvious reasons is that we as a group have fewer financial resources, which means that young people starting out are less likely to get help with a down payment and to need a few more years to save up after high school or college to stash enough cash to get in the game. As far as the "encouragement" factor, I wouldn't put it in the same language as my friend, but yes, it is true that in many instances matters like buying a home, saving or investing are things that just don't get discussed in black households. In short, it does take many of us a lot longer to realize that buying is the thing to do because we haven't been taught the value of it from an early age. I plan to be much, much different with my sons.

That, though, brings me to my next point: While owning a house is clearly an important step that most people should try to take in their lives, I don't believe in homeownership by any means necessary.

Actually, I think that belief -- that everyone should own their own homes, no matter what their circumstance -- is what has the housing market in shambles now. Too many people in the last few years thought they NEEDED to own a crib when they were probably better off as renters.

Homeownership is great, but only under the right conditions, and you shouldn't be trying to buy a house you can't afford. In fact, it can be a terrible move if you're not otherwise financially stable.

Case in point: a study completed earlier this year found that not only are minorities more likely to have subprime mortgages -- basically loans that cost way more than they should for no good reason -- but that high income minorities (that's right, not poor folks, but educated people raking in that cake), are far more likely than poor or wealthy whites to have subprime loans.

This is very dangerous and puts many ostensibly stable black neighborhoods a rate increase away from being filled with foreclosures. And much of it happened because during the inflated housing market of the last few years, too many people who should have been perfectly comfortable renting allowed themselves to be convinced that owning, by any means necessary, was the way to go.

Her theory: "I think it's lack of encouragement. I didn't think owning property was a big deal until my dad badgered me my entire year and a half of grad school to buy something small when I get my first job."

I think there are any number of reasons why we tend to buy our first houses later in life than other groups. First, beware the generalizations -- I know a few black folks my age (in the vicinity of the late 20s, thank you), who already own their houses and have for a few years. At least one person I know owns more than one property. And not every white person, of course, buys their first house in their early 20s.

That said, one obvious reasons is that we as a group have fewer financial resources, which means that young people starting out are less likely to get help with a down payment and to need a few more years to save up after high school or college to stash enough cash to get in the game. As far as the "encouragement" factor, I wouldn't put it in the same language as my friend, but yes, it is true that in many instances matters like buying a home, saving or investing are things that just don't get discussed in black households. In short, it does take many of us a lot longer to realize that buying is the thing to do because we haven't been taught the value of it from an early age. I plan to be much, much different with my sons.

That, though, brings me to my next point: While owning a house is clearly an important step that most people should try to take in their lives, I don't believe in homeownership by any means necessary.

Actually, I think that belief -- that everyone should own their own homes, no matter what their circumstance -- is what has the housing market in shambles now. Too many people in the last few years thought they NEEDED to own a crib when they were probably better off as renters.

Homeownership is great, but only under the right conditions, and you shouldn't be trying to buy a house you can't afford. In fact, it can be a terrible move if you're not otherwise financially stable.

Case in point: a study completed earlier this year found that not only are minorities more likely to have subprime mortgages -- basically loans that cost way more than they should for no good reason -- but that high income minorities (that's right, not poor folks, but educated people raking in that cake), are far more likely than poor or wealthy whites to have subprime loans.

This is very dangerous and puts many ostensibly stable black neighborhoods a rate increase away from being filled with foreclosures. And much of it happened because during the inflated housing market of the last few years, too many people who should have been perfectly comfortable renting allowed themselves to be convinced that owning, by any means necessary, was the way to go.

Wednesday, October 04, 2006

The sweet sound of wedding bells

Months ago, I wrote a story for Heart & Soul magazine about "generational wealth", the concept that your family's ability to help you financially when you're young has a huge impact on your hunt for a piece of Americana.

With lower incomes and less in the bank than other ethnic groups, black folks tend not to give our kids much of a head start. But I never thought about how much that can be attributed to cultural differences until last weekend, when I went to a wedding reception for a 20-something Cambodian couple.

The reception was an hour's drive outside Boston, even though the couple lives in the city. I understood why once I got there. The location, along with everything else about the event, was set up to keep the young couple from having to spend money and to put some get-on-your-feet cash in their pockets.

The restaurant was owned by a family friend, who ate the cost of feeding and liquoring up what had to be 200 people. And gifts be damned: there were envelopes -- the kind you get in church -- at every table. The couple went from table to table, collecting their offerings and saying thanks for the cash stuffed in them.

I couldn't help but think that had I been at a black wedding, there'd be no envelopes and the couple likely would have paid for the whole thing, on their own, on credit.

The experience took me back to my interviews for the Heart & Soul story, in which young, black professional women recalled how they first realized that their families lacked either the means or a plan to help them get on their feet. For some, it was when they saw their white law school classmates get downpayments on expensive homes from parents, while they scrimped and saved for years to buy smaller ones. For others, it was the weddings their colleagues didn't have to pay for out of pocket.

That's where the cultural part comes in. The people at the reception were not wealthy, at least not outlandishly so. They weren't white, and many didn't speak English as a primary language. But they understood that as a community they could do something to help their own stave off debt and get a decent start to their lives. In that instant, they diverged from many blacks by starting a young couple's nest egg for them.

This is something most black folks just don't do, and not because we can't, but simply because this is not how we've been socialized to act.

Call me cynical; I say I'm a realist. I know how we do. And I know that until black folks start doing more to ensure their kids get a decent economic start to their adult lives, we'll continue to lag behind others in this country.

With lower incomes and less in the bank than other ethnic groups, black folks tend not to give our kids much of a head start. But I never thought about how much that can be attributed to cultural differences until last weekend, when I went to a wedding reception for a 20-something Cambodian couple.

The reception was an hour's drive outside Boston, even though the couple lives in the city. I understood why once I got there. The location, along with everything else about the event, was set up to keep the young couple from having to spend money and to put some get-on-your-feet cash in their pockets.

The restaurant was owned by a family friend, who ate the cost of feeding and liquoring up what had to be 200 people. And gifts be damned: there were envelopes -- the kind you get in church -- at every table. The couple went from table to table, collecting their offerings and saying thanks for the cash stuffed in them.

I couldn't help but think that had I been at a black wedding, there'd be no envelopes and the couple likely would have paid for the whole thing, on their own, on credit.

The experience took me back to my interviews for the Heart & Soul story, in which young, black professional women recalled how they first realized that their families lacked either the means or a plan to help them get on their feet. For some, it was when they saw their white law school classmates get downpayments on expensive homes from parents, while they scrimped and saved for years to buy smaller ones. For others, it was the weddings their colleagues didn't have to pay for out of pocket.

That's where the cultural part comes in. The people at the reception were not wealthy, at least not outlandishly so. They weren't white, and many didn't speak English as a primary language. But they understood that as a community they could do something to help their own stave off debt and get a decent start to their lives. In that instant, they diverged from many blacks by starting a young couple's nest egg for them.

This is something most black folks just don't do, and not because we can't, but simply because this is not how we've been socialized to act.

Call me cynical; I say I'm a realist. I know how we do. And I know that until black folks start doing more to ensure their kids get a decent economic start to their adult lives, we'll continue to lag behind others in this country.

Tuesday, October 03, 2006

Blacks get more in Queens, et cetera

First let me apologize for taking such a long time between posts. Now let's get right to it:

1) In what area does he think African-Americans, especially young black professionals are most lacking in terms of financial education, and how can a for-profit bank address that while still making money?

2) The housing market in many cities -- especially DC -- priced out many families looking to buy their first homes, and now rates are rising. Part of the problem was "creative financing" that had people take out loans they couldn't afford while pushing up sales prices. How -- specifically -- can you help both families that can't afford their first homes and those in trouble on mortgages they already hold?

3) This isn't the first effort at targeting the unbanked -- how can you be more successful at getting them through your doors?

4) How can you possibly compete with the Bank of Americas of the world?

- A story in the New York Times this week reported that in New York's Queens borough, the median income of blacks has actually surpassed that of whites. But, the article points out, black immigrants from the Caribbean are doing far better than African-Americans in Queens, and the income numbers might be skewed simply because the most affluent whites have already absconded to Long Island.

- A Baltimore Sun story says the housing boom in that market was largely fueled by minorities, who took an increasing share of the mortgages let by banks over the past year. Good for the housing market and perhaps stats on wealth gaps, but too many of those mortgages were "interest-only", adjustable rate and so on, so there's a real danger the boom could be an even bigger bust for blacks and Hispanics now that rates are up and home values are tumbling.

- Bob Johnson's at it again. The BET founder turned hotel magnate (more on that tomorrow) launched a community bank in D.C. last month. The press release announcing the opening of Urban Trust Bank said it would " be a community financial partner to the diverse Washington, DC community, providing outreach and financial education in a service-oriented environment to build wealth for diverse urban consumers including young professionals, emerging families seeking first home loans and established families seeking second mortgages, single mothers and those who have never established a banking account."

1) In what area does he think African-Americans, especially young black professionals are most lacking in terms of financial education, and how can a for-profit bank address that while still making money?

2) The housing market in many cities -- especially DC -- priced out many families looking to buy their first homes, and now rates are rising. Part of the problem was "creative financing" that had people take out loans they couldn't afford while pushing up sales prices. How -- specifically -- can you help both families that can't afford their first homes and those in trouble on mortgages they already hold?

3) This isn't the first effort at targeting the unbanked -- how can you be more successful at getting them through your doors?

4) How can you possibly compete with the Bank of Americas of the world?

- Upcoming posts: More on Bob Johnson's hotel empire and how his fundraising could open the door for black entrepreneurs, a black financial advisor in Philly sets out to teach money skills to public school kids -- using real cash, and a question from a reader curious about homebuying.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Who's next?

THESE are America's black billionaires. All two of them, according to Forbes magazine's annual list of the richest 400 Americans.

THESE are America's black billionaires. All two of them, according to Forbes magazine's annual list of the richest 400 Americans.This year's list is all billionaires, meaning that for the first time, no one with fewer than 10 digits in the asset column qualified (and they say the rich aren't getting richer).

That only Oprah and Bob -- who needs last names or descriptors to know who they are -- are the only African-Americans in the Billionaire Boys and Girls Club is no surprise. He was the first to join in 2001 after he sold BET; she joined shortly thereafter and that, as they say, was that. For the record: Oprah tied with several other Billies at number 242 with an estimated $1.5 billion fortune, Bob and several others tied for 374th place with $1 billion even, proving, perhaps that it is lonely at the top but not necessarily so for middle of the road moguls.

But seriously, the perpetuity of Oprah and Bob on Forbes list begs a few questions, like when will black billionaires three, four, five or ten join them on the list and where will their money come from? A good percentage of the other Forbes-listers inherited their money, while the others made their fortunes on everything from oil to tech to sports. The lone two African-Americans on the list are self-made media entrepreneurs -- after all, nobody's black daddy until Bob had a billion to leave behind . Will the same hold true for the next to join the list, or will, say, a black investment banker or tech entrepreneur beat the next black media baron to the punch?

And perhaps the better question is when will someone take on the task of ranking the wealthiest African-Americans in the country? (If any of my editors are reading, I'm waiting for your call on this one.) One thing's for sure: we already know who will come in and first and second on that list.

Friday, September 15, 2006

Part 2: 'Brokest' it is

I've finished comparing Black Enterprise's list of the top 10 cities for African-Americans with A.G. Edwards' "Nest Egg Index", which ranks cities where residents are doing better at building wealth against those where they aren't.

Only one city on the Black Enterprise list, Washington, D.C., was also in A.G. Edwards' top ten. It came in at number eight. The only other top black city in the top 100 on the nest egg list was Baltimore, at number 60 -- and those two cities are so close that they're really part of one big metro area. Atlanta, Black Enterprise's number one city for black folks, ranked 123d on the nest egg ranking.

It's hard to say definitively what this all means, but there are a few ways to look at it.

Black folks have smaller incomes, fewer assets, and lower rates of homeownership, on average than whites. So it follows that 'blacker' cities would not fare well in a comparison based on A.G. Edwards' criteria, which factored in a dozen variables -- from income, to home values, to homeownership rates, debt and investment trends .

Many of the cities that scored higher on the A.G. Edwards list did so for reasons that could make them bad places for a young person of any race to try to build a nest egg, and the opposite is true for lower-ranked cities.

Boston, for example, ranked 13th on the list, despite its enormous cost of living and overblown housing market. By A.G. Edwards' standards, higher home values boosted a city's nest egg standing. But Boston would be less attractive to anyone trying to get his or her financial sea legs, while Atlanta, who's lower home values hurt it in the nest-egg rankings, would be much more attractive.

However you slice it, here's what the data showed:

City-- Black Enterprise Rank-- A.G. Edwards "nest egg" rank

Atlanta --1 -- 123

Washington, D.C. -- 2 -- 8

Dallas -- 3 -- 343

Nashville -- 4 -- 303

Houston -- 5 -- 455

Charlotte -- 6 -- 173

Birmingham, Ala. -- 7 -- unranked

Memphis -- 8 -- unranked

Columbus, Ohio -- 9 -- 238

Baltimore -- 10 -- 60

Sources: A.G. Edwards; Blackenterprise.com

Only one city on the Black Enterprise list, Washington, D.C., was also in A.G. Edwards' top ten. It came in at number eight. The only other top black city in the top 100 on the nest egg list was Baltimore, at number 60 -- and those two cities are so close that they're really part of one big metro area. Atlanta, Black Enterprise's number one city for black folks, ranked 123d on the nest egg ranking.

It's hard to say definitively what this all means, but there are a few ways to look at it.

Black folks have smaller incomes, fewer assets, and lower rates of homeownership, on average than whites. So it follows that 'blacker' cities would not fare well in a comparison based on A.G. Edwards' criteria, which factored in a dozen variables -- from income, to home values, to homeownership rates, debt and investment trends .

Many of the cities that scored higher on the A.G. Edwards list did so for reasons that could make them bad places for a young person of any race to try to build a nest egg, and the opposite is true for lower-ranked cities.

Boston, for example, ranked 13th on the list, despite its enormous cost of living and overblown housing market. By A.G. Edwards' standards, higher home values boosted a city's nest egg standing. But Boston would be less attractive to anyone trying to get his or her financial sea legs, while Atlanta, who's lower home values hurt it in the nest-egg rankings, would be much more attractive.

However you slice it, here's what the data showed:

City-- Black Enterprise Rank-- A.G. Edwards "nest egg" rank

Atlanta --1 -- 123

Washington, D.C. -- 2 -- 8

Dallas -- 3 -- 343

Nashville -- 4 -- 303

Houston -- 5 -- 455

Charlotte -- 6 -- 173

Birmingham, Ala. -- 7 -- unranked

Memphis -- 8 -- unranked

Columbus, Ohio -- 9 -- 238

Baltimore -- 10 -- 60

Sources: A.G. Edwards; Blackenterprise.com

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Required Reading, September '06

Heart & Soul magazine, where yours truly is a contributing editor, ran part two of a series called Livin' Large on a Tiny Budget in its August/September issue. I wrote part one, which ran earlier this year.

Essence's Work & Wealth section follows up on its homeownership series, gives tips on raising your credit score and profiles Marsha E. Simms, the first black female partner at New York law firm Weil, Gotshal & Magnes LLP, in its September issue.

Black Enterprise lists the top 50 colleges for African-Americans, names its black executive of the year and leads with a cover story on black supermodels-turned-entrepreneurs in its September issue.

Vibe Vixen advice queen Beverly Smith counsels a 26 year-old reader on getting ready to get a mortgage, in its Fall 2006 issue.

Essence's Work & Wealth section follows up on its homeownership series, gives tips on raising your credit score and profiles Marsha E. Simms, the first black female partner at New York law firm Weil, Gotshal & Magnes LLP, in its September issue.

Black Enterprise lists the top 50 colleges for African-Americans, names its black executive of the year and leads with a cover story on black supermodels-turned-entrepreneurs in its September issue.

Vibe Vixen advice queen Beverly Smith counsels a 26 year-old reader on getting ready to get a mortgage, in its Fall 2006 issue.

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

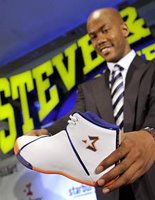

Would you rock these?

Would your kid? Would you buy them if you knew they were endorsed by the N.Y. Knicks' Stephon Marbury? Ok? Well how about if they only cost $15? You heard right. A black pro athlete with a shoe deal -- who's only charging 15 bucks for the sneakers.

Shrewd business move, or image killer? Who knows. Black kids since the Jordan era have typically shunned cheap sneaks. Marbury could be about to take a big loss here. Or, he could be onto something, or just out to make the point that there are more important things in life than shoes that cost more cash than you've got in your bank account. It'll be interesting to see how this one turns out.

Monday, September 11, 2006

Top 10: Best or Brokest, Part One

I wrote recently about an annual survey by A.G. Edwards, the money management firm, which ranks the best and worst cities in the country for building a nest egg. A.G. & crew looked at 12 factors, from the rate of homeownership, to income levels, debt levels, home values, the percentage of a city's population that are investors and the percentage that at least owned savings accounts. Looking at the criteria itself, it was tough to tell whether they wanted to show the best areas to start building a nest egg, or where people already had a good head start at doing so.

Of course, this also got me thinking about whether A.G. Edwards' data could tell us anything else, namely, where black folks stand a better chance of gaining some financial ground, or at least the cities where we're already doing OK.

No, said Sophie Beckmann, financial planning specialist for the firm. A.G. Edwards didn't collect demographic data at all. Fair enough. Still, in her own words, the city-by-city rankings are important because they show where in the country people are getting ahead and where it might be tougher to do so -- important factors in an era when employers and the government are doing less and less to ensure smooth sailing into retirement.

So with that in mind, I'm planning a little experiment. In the next day or so, I'm going to compare A.G. Edwards' list to Black Enterprise's most recent list of the Top 10 cities for African-Americans to see whether the best cities for black folks to live are among the best -- or worst -- places in the country for building a nest egg. I hope to have this wrapped up soon so you can see the results.

Of course, this also got me thinking about whether A.G. Edwards' data could tell us anything else, namely, where black folks stand a better chance of gaining some financial ground, or at least the cities where we're already doing OK.

No, said Sophie Beckmann, financial planning specialist for the firm. A.G. Edwards didn't collect demographic data at all. Fair enough. Still, in her own words, the city-by-city rankings are important because they show where in the country people are getting ahead and where it might be tougher to do so -- important factors in an era when employers and the government are doing less and less to ensure smooth sailing into retirement.

So with that in mind, I'm planning a little experiment. In the next day or so, I'm going to compare A.G. Edwards' list to Black Enterprise's most recent list of the Top 10 cities for African-Americans to see whether the best cities for black folks to live are among the best -- or worst -- places in the country for building a nest egg. I hope to have this wrapped up soon so you can see the results.

Tuesday, August 22, 2006

Minority Rules

I'm reading a new book, "Minority Rules: Turn Your Ethnicity Into a Competitive Advantage", written by Kenneth Arroyo Roldan, the top dog at Wesley, Brown & Bartle, an executive headhunting firm that specializes in finding minority candidates for gigs in corporate America. Like others before it (see Cora Daniels' Black Power Inc.), Roldan's book is all about decoding the corporate labyrinth and unlocking the translucent barriers to success that minorities face as we climb the management ladder. I'm not far enough along in the book to critique Roldan's writing one way or the other, but I do have some context I'd like to lend to his subject.

In most cases I'd be quick to point out the difference between income -- what you bring in each week from a job -- and wealth or net worth -- cash or assets you own regardless of your employment status. But in this case, I think there's an important link between the two. Roldan's advice could be critical to helping more young African-Americans generate some real assets of their own, to the extent it helps anybody get a real job with some real income.

Why? For two reasons: 1) We as black folks tend to have fewer real assets than other Americans and 2) our incomes as a group continue to lag those of whites of the same age. The income and wealth gaps taken together, then, mean that attaining high-salaried management and executive-level jobs like those Roldan discusses in his book is a more critical step for young African-Americans struggling to gain an economic foothold than it is for similarly situated whites -- at least in many cases (there are always exceptions, and certainly not every white kid climbing the corporate ladder was born filthy).

That said, anybody care to share some anecdotes on the comments page about their own push to get a bigger, better job, or if you have one, how much did the salary bump really help you attain some real assets -- a house or stock options, as opposed to say, a new Land Rover with some nice rims?

In most cases I'd be quick to point out the difference between income -- what you bring in each week from a job -- and wealth or net worth -- cash or assets you own regardless of your employment status. But in this case, I think there's an important link between the two. Roldan's advice could be critical to helping more young African-Americans generate some real assets of their own, to the extent it helps anybody get a real job with some real income.

Why? For two reasons: 1) We as black folks tend to have fewer real assets than other Americans and 2) our incomes as a group continue to lag those of whites of the same age. The income and wealth gaps taken together, then, mean that attaining high-salaried management and executive-level jobs like those Roldan discusses in his book is a more critical step for young African-Americans struggling to gain an economic foothold than it is for similarly situated whites -- at least in many cases (there are always exceptions, and certainly not every white kid climbing the corporate ladder was born filthy).

That said, anybody care to share some anecdotes on the comments page about their own push to get a bigger, better job, or if you have one, how much did the salary bump really help you attain some real assets -- a house or stock options, as opposed to say, a new Land Rover with some nice rims?

Wednesday, August 16, 2006

Home sweet...?

There are two homeowners in my family, and as much as I wish it were the case, I ain't one of 'em (Boston home prices be damned).

Still, for us, and probably for thousands of black families, that's progress over a generation ago, when my mother and seven of her eight siblings bounced between rented properties and the projects, where I was raised until I was about 10. By the time I was 13, my moms could finally afford a crib of her own. When I was in college, my aunt and her husband left brick city and moved on up to a nice spot in suburban Pittsburgh, nothing fabulous but nice enough for they and their kids and family gatherings that my mother can't be bothered with hosting.

Given that in my own lifetime my family went from subsidized housing to homeownership, that over the last decade you had to have been under a very large rock to not be lambasted with the advice that homeownership is the best way for families in this country to get their piece of the rock (this is even more critical for black families, which I'll discuss later) and that I got a pretty quick jump-off to my own career, it was only natural that I thought I'd be a homeowner by now. That the housing bubble (I'm coming back to that at some point, too) and those damn Boston home prices have stalled that goal is a big disappointment.

But not nearly as disappointing -- no, staggered -- as I was over the past two days listening to three of my white colleagues talk about buying new homes and selling old ones. That each of them already owned homes was no surprise; the telling thing was that they're all in the process of buying second homes, vacation homes or trading up from one place to a larger, ostensibly more valuable house, that they talked about it with the casualness of a barmaid taking a drink order.

Let me be clear: I'm not hating on my brothers from another color. But it was on some level galling to hear people talk about buying and selling homes (in Boston no less, where the median-priced crib costs a cool half-mil), like they were talking about the latest CD they downloaded.

It brought a lot home for me, thinking about my family members who accomplished so much by buying one house but perhaps so little in because their homes are the only they'll ever own. It makes me wonder if all the talk in the last few years about homeownership being the key to wealth wasn't more than a little overblown, whether no matter how much property my generation of African-Americans acquires, the wealth gap is just too wide to close.

Am I onto something, or just thinking too hard?

Still, for us, and probably for thousands of black families, that's progress over a generation ago, when my mother and seven of her eight siblings bounced between rented properties and the projects, where I was raised until I was about 10. By the time I was 13, my moms could finally afford a crib of her own. When I was in college, my aunt and her husband left brick city and moved on up to a nice spot in suburban Pittsburgh, nothing fabulous but nice enough for they and their kids and family gatherings that my mother can't be bothered with hosting.

Given that in my own lifetime my family went from subsidized housing to homeownership, that over the last decade you had to have been under a very large rock to not be lambasted with the advice that homeownership is the best way for families in this country to get their piece of the rock (this is even more critical for black families, which I'll discuss later) and that I got a pretty quick jump-off to my own career, it was only natural that I thought I'd be a homeowner by now. That the housing bubble (I'm coming back to that at some point, too) and those damn Boston home prices have stalled that goal is a big disappointment.

But not nearly as disappointing -- no, staggered -- as I was over the past two days listening to three of my white colleagues talk about buying new homes and selling old ones. That each of them already owned homes was no surprise; the telling thing was that they're all in the process of buying second homes, vacation homes or trading up from one place to a larger, ostensibly more valuable house, that they talked about it with the casualness of a barmaid taking a drink order.

Let me be clear: I'm not hating on my brothers from another color. But it was on some level galling to hear people talk about buying and selling homes (in Boston no less, where the median-priced crib costs a cool half-mil), like they were talking about the latest CD they downloaded.

It brought a lot home for me, thinking about my family members who accomplished so much by buying one house but perhaps so little in because their homes are the only they'll ever own. It makes me wonder if all the talk in the last few years about homeownership being the key to wealth wasn't more than a little overblown, whether no matter how much property my generation of African-Americans acquires, the wealth gap is just too wide to close.

Am I onto something, or just thinking too hard?

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Who wants to be a billionaire?

The cover story from Business Week's Aug. 14, 2006 issue took me back to a conversation I had with an old boss a few years ago when I was writing about minority businesses as a reporter in Baltimore. The publisher of the paper I worked for at the time -- a white guy in his early 50's -- had just given a speech to a group of mostly black businessmen and in a conversation in his office afterwards wondered out loud why it was that the entrepreneurial culture that sustained immigrant communities like the one his family sprang from hadn't produced the same benefits in black neighborhoods.

One part of that answer, I think, is that black folks in this country still suffer a host of pathologies left over form slavery/Jim Crow/Reganomics/pick-your-period of bad times for black people. But that's way too simplistic an explanation: black folks ain't hardly the only people in the United States who've had it bad, and yet everyone else -- from white Europeans in the 20th century to poor Hispanics with little education and little fluency in English today, seem to realize more than we do that the real way to gaining a foothold in America is through owning homes and businesses.

Which brings me to the Business Week story, about the latest generation of geeks getting rich starting Internet media companies. No surprises here: of the 10 young moguls featured, not a one was black. That, of course, could have as much to do with Business Week's editorial judgment as anything, but giving them the benefit of the doubt, I write for and read Black Enterprise faithfully and can't remember coming across too many stories about young black people with companies outside the entertainment world that are getting valuations in $500 million range.

So I read the story and came across some interesting tidbits: "...the cost of jump-starting a good idea has plummeted. At the same time, the sources of money have multiplied," it says. It explains how Kevin Rose, founder of Digg.com, a company valued at $200 million, "withdrew $1,000 -- nearly one tenth of his life savings" two years ago to start the site, and how he grew up in a three-bedroom flat in "standard middle class America."

So let's get this straight: "Standard middle class" people are starting companies with as little as a grand and an idea, there's money being thrown at them to fund said ideas left and right and the potential payoffs are enormous. Yet, no black folks anywhere to be seen. Anybody got a halfway decent idea why?

One part of that answer, I think, is that black folks in this country still suffer a host of pathologies left over form slavery/Jim Crow/Reganomics/pick-your-period of bad times for black people. But that's way too simplistic an explanation: black folks ain't hardly the only people in the United States who've had it bad, and yet everyone else -- from white Europeans in the 20th century to poor Hispanics with little education and little fluency in English today, seem to realize more than we do that the real way to gaining a foothold in America is through owning homes and businesses.

Which brings me to the Business Week story, about the latest generation of geeks getting rich starting Internet media companies. No surprises here: of the 10 young moguls featured, not a one was black. That, of course, could have as much to do with Business Week's editorial judgment as anything, but giving them the benefit of the doubt, I write for and read Black Enterprise faithfully and can't remember coming across too many stories about young black people with companies outside the entertainment world that are getting valuations in $500 million range.

So I read the story and came across some interesting tidbits: "...the cost of jump-starting a good idea has plummeted. At the same time, the sources of money have multiplied," it says. It explains how Kevin Rose, founder of Digg.com, a company valued at $200 million, "withdrew $1,000 -- nearly one tenth of his life savings" two years ago to start the site, and how he grew up in a three-bedroom flat in "standard middle class America."

So let's get this straight: "Standard middle class" people are starting companies with as little as a grand and an idea, there's money being thrown at them to fund said ideas left and right and the potential payoffs are enormous. Yet, no black folks anywhere to be seen. Anybody got a halfway decent idea why?

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Community banking in the internet age

This week I reported for BlackEnterprise.com on one black executive's three-year journey to create an online bank that would be funded largely by black churches and average-Joe investors and would serve African-Americans in cyberspace. That journey ended when the lead investor in the deal couldn't come up with the cash before a federal deadline forced the bank to have to pull the plug.

Online banks these days are doing pretty good business and they're well-liked by consumers because they kick back interest rates in the 4 to 5 percent range on savings accounts and don't force you to change your arrangement with your regular bank to do so. But with that said, even the man who wanted to start this particular bank acknowledged in my story that there were always questions about whether starting a "community bank" aimed at black folks was the most pragmatic thing to do. After all, brick-and-mortar community banks are competing against the Bank of Americas of the world, and on the Internet, there is no real physical or well-defined ethnic community as there in the real world. So the question stands: how many of you think a black-targeted online bank will eventually be started and survive? And how many of you would use it? Let us know in the comments section.

Online banks these days are doing pretty good business and they're well-liked by consumers because they kick back interest rates in the 4 to 5 percent range on savings accounts and don't force you to change your arrangement with your regular bank to do so. But with that said, even the man who wanted to start this particular bank acknowledged in my story that there were always questions about whether starting a "community bank" aimed at black folks was the most pragmatic thing to do. After all, brick-and-mortar community banks are competing against the Bank of Americas of the world, and on the Internet, there is no real physical or well-defined ethnic community as there in the real world. So the question stands: how many of you think a black-targeted online bank will eventually be started and survive? And how many of you would use it? Let us know in the comments section.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)